Madeleine Oudin, PhD, is Tiampo Family Assistant Professor, Department of Biomedical Engineering at Tufts University and mother to Margot, who was diagnosed with epilepsy at a young age. Here she tells her story as a scientist and mother.

From cancer biologist to rare disease mom: grappling with my daughter’s epilepsy diagnosis

“Your daughter Margot has a mutation in the SCN8A gene, which causes epilepsy”, our neurologist told us. I knew this was a sodium channel, because when I started as an Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Tufts University in 2018 and opened my research lab, I had decided to delve into a new research area, investigating the role of ion channels like SCN8A in breast cancer.

Ion channels control the flow of charged molecules in and out of the cell, which is critical for regulating many cellular properties, such as the activity of neurons in the brain and cardiac cells in the heart. I had spent the previous six years working as a post-doctoral researcher at MIT becoming an expert in the field of breast cancer metastasis, the dissemination of tumor cells in the body, the leading cause of cancer deaths.

I could never have known that this project, coupled with 15 years of scientific training, would provide me with the tools to understand the rare pediatric disease that was affecting my daughter Margot’s brain and that was about to take over our lives.

Madeleine Oudin, Tiampo Family Assistant Professor, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Tufts University, in my research lab in 2018 Photo credit – Alonso Nichols, Tufts University

First signs

A month earlier, when Margot was just three months old, I had woken her up as usual – she had her first bottle and had some tummy time on her mat. I was telling her about France, where I grew up. We had tickets to fly to Paris to see my family in two days. Because of the pandemic, we had not seen them in over a year and a half. Now fully vaccinated and ready to travel, I was so excited to take Margot on her first plane ride, to meet her grandparents and explore her roots.

As I was rocking her to put her down for her first nap, I noticed a repetitive movement in her face; some eye flutters and tongue thrusting. It lasted less than 10 seconds. I figured it was just a weird movement but kept my phone near me just in case. She did it again. Sensing something was wrong and that this behavior was not normal, I filmed it. She fell asleep and I put her in her crib. When she woke up, she did it again and my husband filmed it. We sent both videos to our pediatrician, asking for guidance. She called me back within an hour and said, ‘These look like seizures, get her to the emergency department at Boston Children’s Hospital.’

My heart sank. What was happening to my baby?

Having done my PhD in Neuroscience at King’s College London, I knew a lot about the brain, how it developed, how neurons grew projections or long arms that would attach to other neurons via synapses and form the brain’s connections. Ion channels like SCN8A regulate the flow of sodium into neurons, which modulate their activity. When the flow of ions is dysregulated, this can lead to seizures, abnormal brain activity. I had watched neurons develop and become electrically active in a Petri dish. What was happening with my daughter’s neurons? In my biomedical engineering class, I teach students about this.

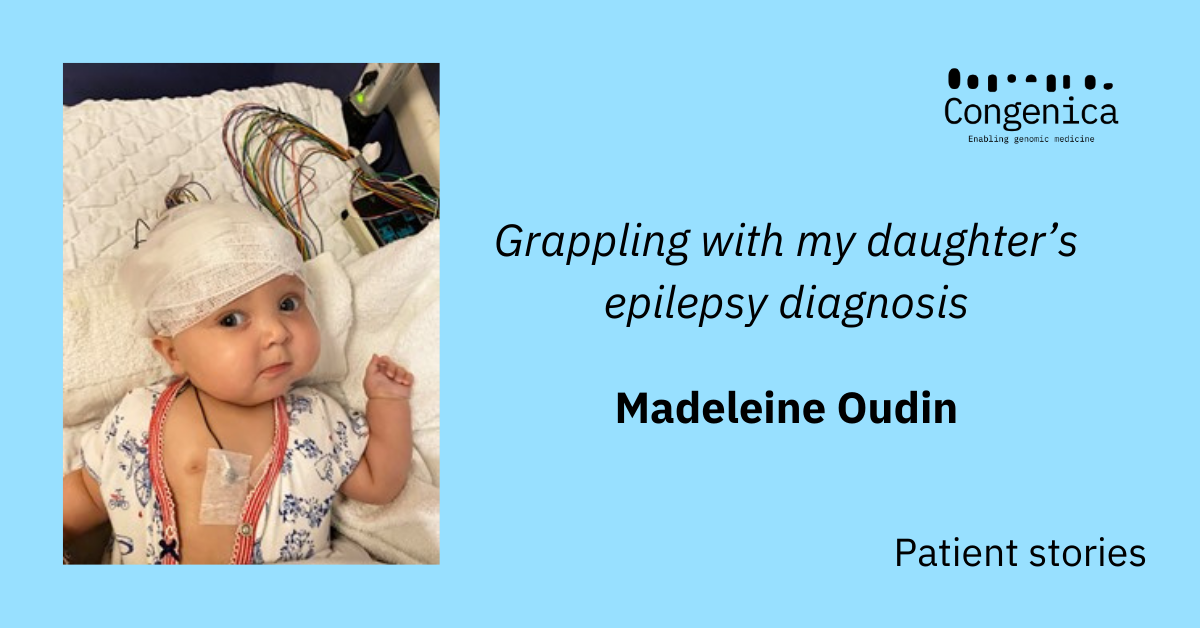

At Children’s, they examined Margot immediately. I joked with my husband that based on my years of watching the medical TV shows ER and Grey’s Anatomy, they would likely admit us for an EEG-an electroencephalogram-to measure her brain activity over time and hopefully catch a seizure to determine the location and cause of the abnormal brain activity. A neurologist came to talk to us and did just that. Margot had a few short seizures while on the EEG and this led to her epilepsy diagnosis. Thankfully, she responded right away to the first anti-epileptic drug the doctors gave her and the seizures stopped.

Margot, five months, during an EEG at Boston Children’s

Searching for a cause

Now we needed to find the cause. First, they did an MRI to rule out any structural damage. They let me sit in a chair close the machine in the main room, in a hospital gown, covered in warm blankets, listening to the rhythmic loud noises of the machine.

The scientist in me could not stop thinking about the power of biomedical engineering in helping my daughter. Between the EEG, the drugs, the MRI, decades of basic biology knowledge and technological innovation had enabled these tests and the development of these drugs that could so quickly and accurately tell us about what was going on in her brain and provide medicines to treat it.

As a cancer researcher, I was terrified that she might have a tumor.

As a mom, I just sat there and cried, never having thought I would ever go through something like this, hoping my daughter would be healthy.

The MRI came out normal, so they sent out metabolic and genetic testing just in case, but the doctors said it was unlikely we would determine a cause. As a scientist, I know that the statistical chance of her having a rare mutation that would be detected by these tests was incredibly low. There was no history of seizures on either side of the family. The clinical team said she would likely be on this anti-epileptic drug for one-two years and the seizures would go away.

We had to cancel our trip to France but went home and were so grateful that we caught this early, that the seizures had responded to the treatment, and that the MRI had not revealed any issues with her brain. We had another trip planned to go visit my husband’s family in California, and at our four-week follow-up our doctor gave us the green light to go. I was so excited to travel, take my daughter on a plane and start exploring the world with her.

Genetic testing delivers unexpected results

Four days in to our trip, we got a call with the genetics results: our daughter had mutations in the SCN8A sodium channel gene. Not just one, but two mutations that changed the protein sequence, which we later confirmed were spontaneous or de novo, meaning that we had not passed either of these mutations down to her.

Having a mutation in the coding part of the SCN8A gene is very rare, like being struck by lightning, but when it happens it very often causes epilepsy and wide range of other problems. Margot, with her two mutations, was hit by lightning – twice. My amazing, kind and supportive husband, Chris Burge, is also a scientist, a Professor of Biology at MIT. We spent the entire day and next few weeks researching this ion channel, using PubMed, a popular search engine for biomedical publications. To our surprise, a lot was known about SCN8A, with many researchers all over the world working on trying to understand how genetic mutations cause epilepsy and trying to find new treatments for children affected by these diseases.

Dr. Michael Hammer, a geneticist at the University of Arizona, discovered that a mutation in this gene caused his daughter’s seizures, identifying SCN8A as an epilepsy gene. He immediately started what is now a mature longitudinal registry that is accelerating the pace of understanding of this ultra-rare disorder. A professor at the University in Michigan, Dr. Miriam Meisler, has been studying the function of SCN8A since the 1990s. Another scientist in Denmark, Dr. Rikke Moller, is testing out the effects of different mutations to try and predict the progression of the disease.

There are about 500 cases of children with SCN8A mutations reported in the world, most of which can cause seizures with a range of severity, developmental delays and intellectual disabilities.

Understanding SCN8A mutations

As a mom, I was devastated, so angry that biology, a subject I had committed my life to studying, had failed us –had failed Margot. I hugged my daughter tighter than I ever had before. In my biomedical engineering class, I also teach about how mutations happen in DNA, how molecules that repair our DNA to prevent these mutations from happening can make mistakes –it’s just bad luck. But as a mom, I kept thinking –why my daughter? Why us? As a scientist, I knew there was no good reason–nothing we could have done to prevent this –it’s just random, just bad luck.

As scientists, we wanted to know where in the SCN8A channel Margot’s mutations are–because different parts of the gene impact function in different ways. One mutation is in a part of the protein where few mutations have been described, making it hard to assess. But the other mutation occurs in a small loop outside of the cell, where other nearby mutations have been described as causing epilepsy. This mutation affects a portion of the SCN8A gene called exon 5N, where the N stands for “Neonatal”, meaning that this mutation affects a version of the protein that is expressed predominantly in fetal and early childhood development but is gradually replaced by a different version of the protein (which is normal in Margot’s case) during adolescence and adulthood. The process by which this switch is regulated is called RNA splicing –a topic that my husband Chris has been working on for 20 years in his own research lab. In fact, his lab has recently published a study on the protein that is known to regulate this splicing switch in SCN8A.

Interestingly, there are many other genes that have neonatal and adult versions. These neonatal versions have been found to play a role in some cancers –where tumor cells revert to a more primitive state and behave more like a developing organism as opposed to an adult tissue. I had spent my post-docat MIT studying one of these neonatal genes that was important in brain development and is then reactivated in cancer. I was recently awarded a New Innovator grant by the NIH to look at the role of neuronal genes in cancer.

Research and support

To us, this was all crazy coincidence. As we delved deeper into the published literature, we were continually surprised by how closely related our daughter’s mutation was to our scientific expertise. This coincidence gave us the unsettling (and irrational) but unavoidable feeling that this somehow happened for a reason. It feels like my entire scientific career has been in preparation for this –for my daughter.

As a scientist, I am digging into the data to better understand my daughter’s mutation. We have found some anti-epileptic drugs that work for her, but others that did not, some have very severe side effects. We have a fantastic clinical team at Boston Children’s with whom we can have in depth discussions about the science and the medicine. I also know that several companies are actively working in this area to develop new drugs for this disease, such as Xenon/Neurocrine Biosciences and Praxis Precision Medicine. As a scientist, having a deep understanding of the biology of SCN8A, the drugs that treat it, the ongoing research, helps me feel more in control.

As a mom, what has helped me the most, are the parents of children with SCN8A epilepsy and other rare diseases. I have been blown away by their kindness and support. I am so grateful for the parents who have come before me and started foundations to support children affected by SCN8A epilepsy, such as Wishes for Elliott, now the SCN8A International Alliance and the Cute Syndrome Foundation. I am listening to podcasts, following Instagram accounts of fellow rare disease moms, and learning how to navigate my new role as a rare disease mom. So, I am jumping into the rare disease community, joining the fight, sharing my story, raising awareness. It is still early on, and I am trying to find the best way that I can make an impact and advocate for Margot. I will do everything I can to help my daughter navigate this diagnosis and keep hoping that she can find joy and thrive.

This is not the life I wanted for her, the life I pictured for her, but I know she will leave her mark in this world and that her journey, our journey, will bring us one step closer to a cure for SCN8A epilepsy.

The day before our diagnosis: family picture with sleeping Margot in one of our favorite spots: the Cactus Garden at Stanford University in Palo Alto California

The day before our diagnosis: family picture with sleeping Margot in one of our favorite spots: the Cactus Garden at Stanford University in Palo Alto California

Support groups

If you have been affected by SCN8A, there are support groups and organizations that can help you, including:

Patient Advocacy and Engagement at Congenica

A desire to improve the lives of people living with rare and inherited diseases is central to everything we do at Congenica, and our patient advocacy and engagement initiative aims to ensure the patient voice is heard loud and clear inside the company.

We also want to help patients navigate often confusing and disparate information by providing educational materials that are trustworthy and helpful. Our aim is to ensure patients, clinicians and researchers understand the patient journey from referral, through diagnosis and beyond.

We strive to help ensure all parties understand the strengths and current limitations of genomic medicine as well as ensuring we work together to realize the full benefits that the genomic revolution promises.

To keep up to date with our news, including the latest blogs, sign up to our Patient Advocacy and Engagement newsletter.

The day before our diagnosis: family picture with sleeping Margot in one of our favorite spots: the Cactus Garden at Stanford University in Palo Alto California

The day before our diagnosis: family picture with sleeping Margot in one of our favorite spots: the Cactus Garden at Stanford University in Palo Alto California

.png?width=320&height=192&name=Untitled%20design%20(8).png)

.png?width=320&height=192&name=Webinar%20the%20cost%20of%20rare%20disease%20(2).png)

.png?width=320&height=192&name=Patient%20stories%20(2).png)