Lynsey Chediak is a Member of Congenica’s Patient Advocacy and Engagement (PAE) Advisory Board as well Head of Partnerships at Rarebase, which enables rare disease therapeutic discovery and development. Here she tells us her story of living with a rare, genetic joint disease called arthrogryposis.

The moments when time stands still

On the morning of Tuesday, March 16, 2021, I sat alone in the pre-operative room of the University of California, San Francisco’s famous metropolis of a hospital in San Francisco, CA. Minutes away from having surgery on my brain and neck, my anesthesiologist walked up to give me the final pep talk before I’d be wheeled back to the operative room (or ‘OR’ as it is called in the USA).

The anesthesiologist passively mentioned that she planned to keep me on a ventilator overnight so that I wouldn’t have to endure too much ‘unnecessary pain’. She warned, “you will likely wake up on Wednesday, not Tuesday, and it will be as we’re pulling out a breathing tube from your throat. Try to stay still during that process, okay?”. My mind started racing. This was in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, so I knew all too well about ventilators. How could my medical team just be mentioning this for this first time? As usual, I had to face this alone.

I inhaled slowly, and prepared to reply, but paused—distracted by the nurse who was poking me with a needle, once again attempting to put a second IV in my petite left arm at the same time. I calmly responded: “I’d prefer to wake up today and not be kept on the ventilator overnight. This is my 31st surgery. I can handle the pain.”

I woke up roughly nine hours later in the intensive care unit (ICU) with six new vertebrae bones in my neck from a generous bone donor and lots of permanent titanium to make sure my neck would never unexpectedly break again (especially since the break had squished my brain stem in the process). I was unable to open my eyes because they were so swollen, but I was overjoyed by the sensation of my fiancé’s hand squeezing mine and his voice telling me that the surgery had been a success. I couldn’t believe what I was feeling; I hadn’t been able to feel my hands or the touch of his hand for the past year since my neck broke without warning. I quickly squeezed his hand back—another thing I hadn’t been able to do for a year.

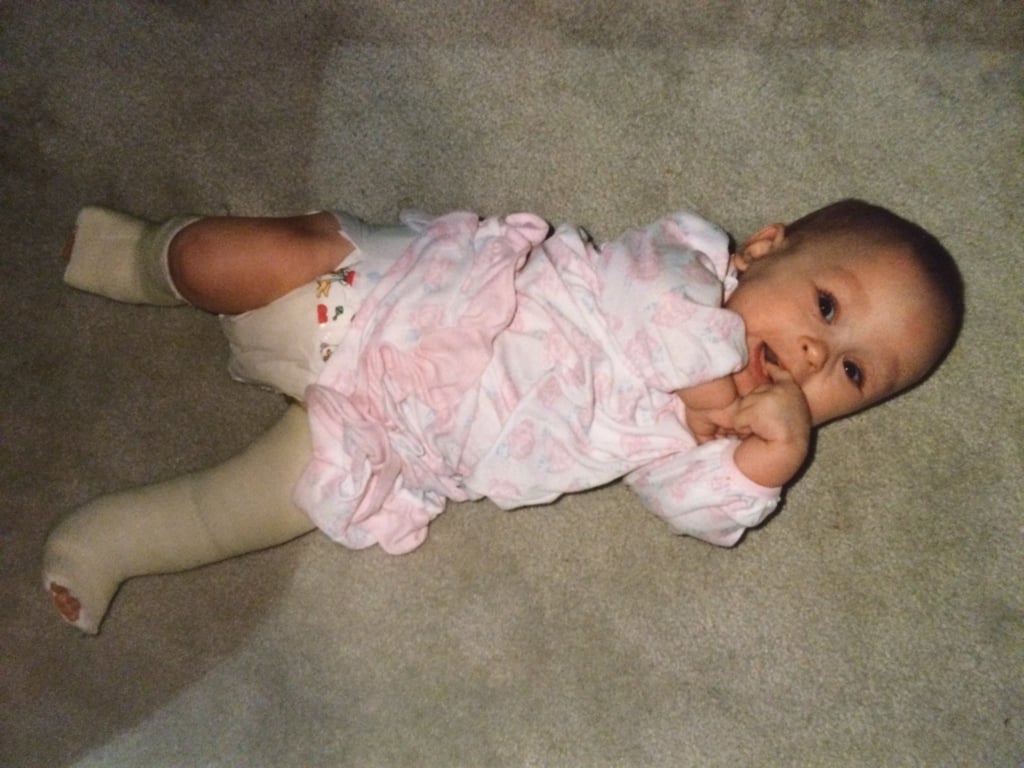

There is only one word that can explain why the neck of a 28-year-old female collapsed on itself: arthrogryposis. I was born with a rare, genetic joint disease called arthrogryposis. I entered this world with nearly every single bone in my body bent and fixed with extra fibers in every joint. Even as one of the less severe cases of arthrogryposis, I was born with a bent neck, bent arms, bent hands, bent wrists, clubbed feet, bent knees, bent hips, and, as a bonus, a collapsed lung.

Getting diagnosed with a rare disease

Thanks to modern medicine, a team of four skilled neurosurgeons successfully replaced the bones in my neck with new, healthy, straight ones without killing me; yet there is so little research being done on rare diseases that I don’t have a treatment – nor do roughly 380 million other people living with a rare disease globally.

As a child, I didn’t fully realize that I had something ‘different’ about me. For the first four or five years of my life, I felt like a regular kid. Even with an unaffected fraternal twin sister, I wasn’t readily aware that every kid wasn’t also going to countless doctor appointments (not to mention flying across the country to see experts) and struggling to do basic life things like move from my bedroom to the kitchen on the other side of my parent’s house.

When I woke up every morning as a kid, I often couldn’t move because my bent joints were too stiff from lack of movement. My Mom would kindly carry me into the kitchen for breakfast. I used to think how nice it was – waking up greeted by a hug and a free lift to the kitchen! It never crossed my mind that other kids could wake up, step out of bed, and start their day on their own without help.

When I was five years old, a diagnosis finally resulted when a children’s research hospital hosted a multiple day symposium to attempt to understand my condition. There was a man dressed as a clown at the door who handed out stickers and a giant art mural with all of my favorite cartoon characters—including my personal favorite Tweety Bird—which I could spend hours staring at in between appointments. My doctors always ended my appointments by reminding my parents we should stop for a treat like ice cream on the way home (which we almost always did). I never thought to ask why I was there because it had been a presence in my life since I could remember. Oddly enough, the smell as I hobbled my way into the hospital with a walker brought me joy every time. To me, the smell of the hospital with its rampant odor of disinfectant smelled familiar; it almost reminded me of a second home.

I remember being in the hospital’s auditorium in a bathing suit with 15 doctors surrounding me. One by one, each would come up to me and ask me to lift my bent knees or lift my bent hands or try to hold a cup—something my hands wouldn’t bend enough to do. They told me they had never seen bones like mine, which I initially took as a compliment. I didn’t know why these doctors were interested in me, but I was happy to help them learn.

Although a diagnosis was helpful, arthrogryposis is one of the nearly 7,000 rare diseases without a treatment option available. While I had a name of a disease to reference, no doctor had heard of the disease or could suggest a treatment that would allow me to walk. I didn’t really know what arthrogryposis meant or understand the series of surgeries that the doctors recommended to my parents as exploratory treatment. By the time I entered kindergarten, all I knew was that I couldn’t walk like my twin sister. No matter how many doctors my parents and I met with, no one could tell me why.

My desire to walk shaped my entire childhood. I didn’t get it: why couldn’t I move? Why couldn’t I move my legs like my parents, sister or my friends? By the time I was in kindergarten, I refused to use a walker because I noticed that none of my classmates had one. If they didn’t need one, why did I? I would watch my classmates sprint out of the classroom to the playground at recess. Meanwhile, I could barely stand on my own without toppling over. When I did manage to stand, I was hunched over with bent knees, bent hips, and wobbly, unstable feet.

Living with a rare disease

When I get asked what it’s like to have a rare disease, I never know quite what to say because it’s all I’ve ever known in life. Living with a rare disease ultimately means that I don’t know what a normal body feels like. All I know is this body that I was born into – and that creates a lot of problems for understanding what is ‘normal’ and what is not.

I’ll never forget the first time I stood up straight when I was 15 years old. At last, an exploratory treatment worked after more than a dozen surgeries had failed. I was able to stand straight and, after much physical therapy, take my first steps to walk. I was grateful, but also disappointed. How did everyone else enjoy this magical gift so easily? The freedom of walking meant I could go shopping to get my own clothes without extreme pain, walk next to my classmates at school in between classes or stand over a counter to pour my own cereal into a bowl without shaking. It was simply miraculous.

Now that I have been walking for over a decade throughout the second half of my life, I am incredibly frustrated by the lack of treatment options to similarly grant the magic and freedom of walking to other children living with rare joint and bone diseases. How did one fluke exploratory surgery work on me? Why isn’t it a new standard treatment for my rare disease? The research and knowledge sharing that is common and essential for other disease areas simply is not replicated and does not exist in the rare disease space.

The hope that genomics can finally deliver answers — and more

Genomics has fundamentally changed what it means to live with a rare disease. For once, I have a definitive answer on what caused my disease: a single gene that is different in my body than in most other humans. A gene called PIEZO2 is responsible—and, by better-understanding that gene, there is the opportunity to discover the solution for how to alleviate or even prevent my symptoms.

For my first 28 years in this world, I had a disease name called arthrogryposis, but no cause and no treatment. Now, I have a confirmed genetic diagnosis. By knowing the causative gene for arthrogryposis, it may be possible to investigate potential treatment options. By finally understanding the cause—going beyond the current standard of only diagnosing the symptoms, often referred to as the phenotype—there is an opportunity to finally develop treatments.

After all, if I had a treatment, I wouldn’t have to wait for my bones to break. If I had a treatment, my medical team could prevent my bones from breaking and prevent the disease’s ability to wreak havoc on my body causing intense pain and adverse symptoms like limited or no physical mobility.

The power of genomics can help remove the mystery of the roughly 80% of rare diseases that are of genetic origin and do not have treatments or cures. If we can understand how a change in a single gene, also called a genetic variant or gene mutation, impacts the human body, it will be possible to develop treatments that are personalized for each person living with a rare disease. Genomics—and understanding our individual, one-of-a-kind DNA—will allow clinicians to deliver medicine that is truly personalized.

I am proud to work at a biotech company called Rarebase that is attempting to develop treatments for children living with rare diseases based on the human genome and the specific genetic mutations that cause rare diseases. Our company believes that the starting point is always to partner with the patient, and then bring the latest in technology and translational science together. It takes a village to make this dream a reality, and we still have a long way to go to embrace the reality of using precision medicine to help all of us with a rare disease get better.

While I am grateful to be able to walk and to have new bones in my neck (not to mention the bone transplants in prior years in my feet and face), I want to make one point clear: it did not have to be this way. I did not need to undergo 31 surgeries in my short life. If there was a treatment for my disease, I wouldn’t have had to experience the excruciating pain of my neck collapsing on itself—or the yearlong delay of living with a broken neck while my medical team figured out what to do amid an absence of an expert on my disease. If there was a treatment for my disease, I would’ve been able to spend my childhood walking, exploring, and playing with my friends, rather than constantly being trapped in my own body and unable to move.

We must embrace the power of genomics at both the diagnostic and therapeutic levels. The revolution of precision medicine is finally here. And we must use it, now. I know another bone in my body will break without warning, so it’s just a matter of when it will happen and what else will be damaged in the process. In the meantime, I am still one of the 380 million people living with a rare disease without a treatment—waiting.

Lynsey Chediak is a Member of Congenica’s Patient Advocacy and Engagement (PAE) Advisory Board as well Head of Partnerships at Rarebase, which enables rare disease therapeutic discovery and development.

Patient Advocacy and Engagement at Congenica

The role of the PAE Advisory Board is to be the critical friend of Congenica, ensuring we serve patients to the fullest of our abilities. The board will inform product development and communications to make sure they serve patients as best they can. Board members also help guide the development of helpful content about genomic medicine and the patient journey. Our goal is to become the go-to, trusted source of information for both patients and clinicians.

For more information on our PAE work, sign up for our newsletter.

%20Advisory%20Board%20as%20well%20Head%20of%20Partnerships%20at%20Rarebase%2c%20which%20enables%20rare%20disease%20therapeutic%20discovery%20and%20development.%20Her.png)

.png?width=320&height=192&name=Untitled%20design%20(8).png)

.png?width=320&height=192&name=Since%202016%2c%20the%20number%20of%20women%20working%20in%20STEM%20fields%20in%20the%20UK%20has%20increased%20by%20216%2c552%2c%20taking%20the%20total%20number%20over%20the%201%20million%20mark%20for%20the%20first%20time.%20Women%20now%20make%20up%2024%25%20of%20the%20STEM%20workforce%20i%20(2).png)

-1.png?width=320&height=192&name=Deciphering%20Developmental%20Disorders%20(1)-1.png)